Breakthroughs & Setbacks: How and Why We Should Bring Back Skill Challenges. Kind of.

Some skill checks answer simple, immediate, yes/no questions. Do I see that goblin hiding in the bushes? A 15 — why, yes, I do. A simple yes/no die roll is appropriate and satisfying for those situations.

But a single check doesn’t always feel right for other situations, particularly those involving ongoing, progressive challenges in which failure could happen at any time, with consequences.

- I can fail my attempt to scale a building at any point, but it hurts a lot more if I fail near the top.

- Similarly, it feels weird to have one roll to climb a 10-foot wall and then to also roll once to scale a 1,000-foot cliff-face.

- A single check to disarm a complicated trap often feels anticlimactic and out-of-sync with a combat system that might require several swings to dispatch a complicated monster.

I’m not the first to try to complicate such scenes. D&D has taken several shots at it. The most well-known experiment was 4th edition’s skill challenge system. Fifth edition’s designers fell violently out of love with that experiment, though they clearly still agreed with its goals.

How do you feel about skill challenges going forward?

Rob [Schwalb]: (jokingly) I really want skill challenges to die in a fire. The plan was great for those, but I always felt it subtracted too much from the narrative. I think we can do complex skill checks within the narative and provide a robust amount of information to help the DM just weave them into the story.

Monte [Cook]: The only thing I would add is that I don’t want to take away from the idea of a player saying “I want to do this thing”. And the DMs response isn’t just “well make the check and you do it”.

From a transcript of a Reddit AMA with designers of the 5th edition of D&D.

The 5th-edition approach is old-school: players narrate what they want to do and GMs adjudicate, sometimes awarding Advantage if the narrative is appropriate and clever. But it’s often still a single check.

Sure, a clever or experienced GM, drawing on examples from other games or other editions, might divide a trap into three components, each of which need to be defeated somehow (and not necessarily by someone with thieves’ tools). But for newbie GMs, the current edition doesn’t provide much of a toolbox for the kinds of complicated skill resolutions that I tend to think of as thieving checks. (I call them this because many of the skills that sometimes beg for a complicated approach were once exclusive class features of the AD&D Thief class.)

I agree with DMing with Charisma: Game designers almost had a good thing with skill challenges. The idea of a target number of successes often makes sense, and having three failed checks lead to failure of the entire challenge gives a GM a handy, reusable mechanic. DMing with Charisma’s analysis of what was wrong with the original experiment is insightful, but I think the system had some other problems.

- It ensured every skill challenge took a predictably long period of game time. Compare this with the rhythms of combat: It’s possible to get lucky and kill off an ogre quickly. It’s possible to get squashed by an ogre early in a combat. That means a combat with an ogre has a variable duration. That variability helps keep combat (which is also a series of die rolls) from getting too stale. When every skill challenge might take 9 to 10 turns, that predictability dulls the experience.

- It assumed every skill challenge needed to be a challenge for the entire party. I totally understand the idea here: You don’t want to leave some members of the party twiddling their thumbs. But in most other skill-resolution systems, this isn’t a danger. Truth be told, group boredom only became a danger because of issue #1 above: The skill challenge system often would take 5-10 minutes of game time, so designers had to frame the entire system as a party challenge to keep folks at the table. An artificial problem begat an artificial solution. This in turn led to…

- Paladins trying the weirdest skill applications ever in an attempt to defeat a trap.

In the end, we went from

(A) a single check for a single challenge being resolved by a single player

to

(B) long scenes in which five or six characters would try five or six times each to resolve that challenge

–often without much improvement in game narrative.

Drawing on the same kind of approach I used for Smarter Intelligence Checks, I want to propose a simpler way to deal with “thieving-check” situations, one that complicates the scene enough to add drama but which doesn’t necessarily take a lot of table time. By combining this approach with another tip (which I’ll mention later), I think you can enjoy the complication of a skill challenge without its tedium and labor.

Incremental Success

The Incremental Success system works best for complicated challenges that ought to require both time and multiple stages of work to complete. It doesn’t work for every skill or every situation.

Some quick definitions:

- Breakthrough: Each successful check during the challenge is a breakthrough. Collect enough breakthroughs and you succeed at the challenge.

- Setback: The opposite of a breakthrough. Gain three setbacks and you’ve failed the challenge.

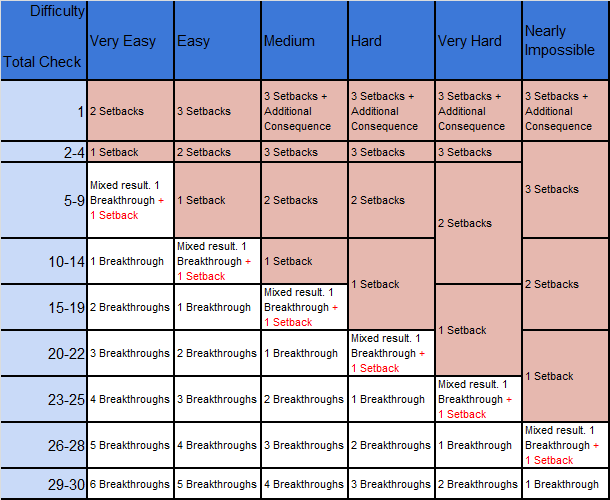

- Determine the difficulty of the challenge (Very Easy, Easy, Medium, Hard, Very Hard, Nearly Impossible) and the number of breakthroughs required to succeed at the challenge. One way to think of this: The difficulty of the challenge is kind of like a monster’s Armor Class, while the number of breakthroughs is like its hit points.

- When a PC rolls a check, compare it to the table below. Note that in the Incremental Success system, it’s possible to achieve multiple setbacks or multiple breakthroughs in a single check.

- If the PC accumulates 3 or more setbacks, she fails. If she collects the target number of breakthroughs, she succeeds. If neither has happened, she continues rolling checks until she meets one of those two thresholds.

Some quick remarks about using the above table.

- Additional Consequences. This means that, in addition to failing the challenge, something else bad just happened. For instance, someone falling off a cliff might pull another climber off with him. Ouch.

- Mixed Results?? Yes, the table means that some rolls will result in both a breakthrough and a setback at the same time. This sort of thing happens all the time in real life. You veer at the last possible second, avoiding a head-on collision with a truck — and end up going the wrong way on a one-way street. Half of the “successes” you see in a movie are this sort of mixed result. So why not have them in your game? They’re fun. If this kind of roll results in a PC getting 3 setbacks and the target number of breakthroughs at the same time (which is possible), have her roll a final do-or-die check, treating any further mixed-results as a by-the-skin-of-the-teeth breakthrough. The character is in peril, hanging on by fingernails.

- GM Restraint. It’ll be tempting to pick high-level challenges and set large breakthrough requirements. Resist that temptation. For instance, if you require more than 3 successes, your challenge will now be more difficult than your difficulty level implies: It’s really about one level more difficult. That’s fine, but you don’t want to do that unintentionally. Moreover, it can be fun to require just one breakthrough, particularly for difficult challenges. You only need to succeed once, but there’s a limit to how much you can screw up before things go pear-shaped. That can be fun. And a GM could run a great low-to-mid-level campaign using only the Easy column, simply raising the number of breakthroughs required as the party gained levels.

- Teaming Up. If the challenge is one that could plausibly be pursued by several people working together, it’s fine to let several PCs roll in an attempt to gain breakthroughs more quickly. Just add them together. Add their setbacks together, too, though!

- Timetables. The challenge takes on dramatic urgency if it’s on a clock. For this reason, it’s a good idea to decide how long each check takes. The default is probably a turn, but for some checks it might be more appropriate to have each one take a day or an hour. (For instance, if the party is trying to find the camp of bandits plaguing a particular forest, their search might take many days.)

- Levels of Consequences. It’s a good idea to work out ahead of time what it means to fail at the challenge, and even better to work out different consequences, depending on when the failure happens. Falling from 90 feet is different from falling from 10 feet.

- Narrative Flavor Text. Similar to point 6 above, you might decide why the task requires the number of breakthroughs you’re requiring and what each check means. Maybe the first check in scaling a cliff is planning the route. A setback there might mean the climber realizes mid-way up he’s not on the optimum path and will need to be careful to avoid falling. Maybe the third check in that climb involves navigating an overhang 200 feet above the ground. A trap requiring four breakthroughs might have one primary trigger for the unwary passer-by, plus three other triggers for anyone attempting to disarm it, each of which needs to be disarmed before the obstacle can be passed.

Although the above tool permits multiple PCs to work on a challenge, I’ve assumed that a single PC will usually be attempting it — mostly because, outside of social encounters, that’s how it has tended to work, except in 4th edition. (I’ll deal with social encounters in a later column.)

Wait. What’s Wrong with Solo Monsters?

The solo encounter issue has been a long-standing and much-discussed problem across many editions of the game. For some online commentaries about the problems that GMs often have with solo encounters, see here and here.

And that’s a good thing. A group challenge may involve everyone, but it’s rarely satisfying. The problem with the party-sized skill challenge is the same as with a solo monster: Often, the game’s fun breaks down when all of the players are concentrating on the same problem. That way lies insanity.

If you want to keep everyone busy, a better approach is to challenge each PC in a different way in the same scene. While the rogue is fiddling with the trap, the wizard is trying to decipher runes so they know which way to go once the trap is disarmed, the fighter and ranger are holding off orcs, and the cleric is trying to diagnose what kind of undead killed their barbarian.

That way, the party’s rogue can really feel the pressure when he rolls a setback.†

♦ Graham Robert Scott writes regularly for Ludus Ludorum when not teaching or writing scholarly stuff. Graham has also written a Dungeon Magazine city adventure titled “Thirds of Purloined Vellum” and a fantasy novella titled Godfathom. Like the Ludus on Facebook to get a heads-up when we publish new content.