Raicho the Recusant

An Experiment with Narrative

Because character is best revealed through narrative, I thought I’d present most of this installment of Dice Unloaded in story form. It’s an experiment.

Raicho the Recusant—fourth and most controversial in my ongoing series on reskinned clerics—is a divine mercenary, fiercely independent and beholden to no single god. Instead, temples hire him, and he channels divine power from whichever god he happens to be serving at the moment, assuming the god in question or its seneschals are open to the idea—which they sometimes aren’t. It’s a disreputable line of work.

The setting for the narrative is the city of Eador, in the Vorago. Below the narrative, I’ve included a commentary on the rules-based rationale for such a cleric. Here, you can find some stat blocks for Raicho at 1st, 5th, and 10th levels, with the OGL located here.

Guest-starring in this piece is Savina, disciple of the Shackled Lord, whom I haven’t written up yet, but may.

It was dusk when Savina left the High Amble to step gingerly down the uneven flagstone stairs from the boulevard’s sharpest bend onto Red Weeper Row.

Above and behind her, she could hear merchants’ wagons taking the bend, wheels clacking as they slipped in and out of the ruts. Before her, in shadows, huddled the basement shops and homes of the Lower Whitecandle district.

Hurrying to a deep shadow between two buildings, Savina tugged her hood down to better hide her face and looked back toward the stairs.

The figure approaching the top of the steps had the same bearing, same build, same height, and same gait as the man she had spotted lurking outside the Fane of the Grail Duchess, but his face and clothing were different.

She shivered. This was the third such sighting today.

A different man? she wondered. Or the same man in a new guise?

Or something worse?

Savina pushed that last thought away, turned and strode down down Red Weeper, following its gentle curve and slope.

Here and there, shopboys brought out brass filigree eggs, illuminated from within by captured mini-wisps, hanging them from hooks below their swaying, wooden signs. Then they locked their doors and scurried along. No horses or carts clogged the traffic on Red Weeper, unable as they were to descend the steps, and that left the route mercifully clear of dung. Not surprisingly, then, the road, once an alley of surgeons, had evolved over time into a haven not just for medicine, but also for the selling and enjoyment of food and drink.

Two corners later, where steep-and-narrow Scalpel Alley tumbled into the Row, Savina passed through an archway into a crowded courtyard.

Most of the people here seemed harmless. Neighborhood regulars had gathered to feast on a hale ram brought in by a hunter from the hills outside the city, a local vintner and brewer had each uncasked some version of liquid fire for the occasion, grocers had brought up black salad from the Undergardens, and the residents along the courtyard had hauled out tables and chairs for visitors to rent. Residents filled bowls with hale-ram stew and cups with spirits, tossing coins into cold smudgepots by each vendor.

Nevertheless, Savina appraised a half-dozen-or-so people in the courtyard as potentially dangerous.

Four men of the Open Tomb Society—a brash band of ruffians and mercenaries who had recently taken over a local tenement—boasted and jostled over dice. Nearby, an armed couple bearing the crossbow-shaped cloak pins of the Closet Council drank quietly, watching the Open Tomb gang. Savina gave both tables a wide berth, unwilling to get caught in the crossfire if the two criminal organizations began fighting.

The last dangerous figure sat alone in a corner, shield leaned against the courtyard wall. He had no food, nor drink, yet had jabbed a coin into the wax midway down the rent-candle to claim his seat. A Vulchum machete lay across the table, sheathed. Watching the two other tables, the man scratched idly at an itch under his breastplate before he spied Savina. He studied her for a second or so, before turning his attention back to the tables of thieves.

Savina glanced back toward the archway, but saw no one who might be her mystery pursuer. Turning her attention back to the man in the corner, she compared his features with those she had heard described by contacts: a broad, if crooked, smile; a stubbled jaw and pate; an array of tattoos and ritual scars on both hands and up the arms. Wrapped around one forearm, a chain of prayer beads held religious symbols and icons of multiple gods. Savina swallowed her distaste, approached, and sat across from him.

A moment passed before either spoke.

“I’ve been told you’re the Recusant,” Savina finally said. It sounded rude, like an insult, to her own ears, but the man merely nodded.

A freelance priest, mercenary to the gods. She had only heard of three such people and one of those had been dead for centuries.

“May I see them?” she asked, gesturing at the prayer beads.

One of his eyebrows rose briefly, but he slipped the chain off his arm and slid it across the table to her. She inspected the icons.

“The scroll, the mask, the grail. Not sure what that one is. The Magister’s cross. The eye,” she inventoried. Finally, she held up one piece, almost daring an explanation: “The rook.”

The man reached over and pushed up the sleeve of Savina’s robe, exposing a metal band around her arm, two links of chain dangling from it. A fetter. “And you wear the Shackle,” he noted. He let the sleeve fall back into place.

“You don’t have that one,” she said.

“Not yet,” he answered. “If you need me for a job, and if I agree to do it, you’ll have to get me one of those.”

She considered. The gods whose symbols he bore had some tensions and rivalries with each other, but he didn’t seem to have any of the truly bad ones. Nothing from the Barrow Dragon; no scepter of the Outcast King.

“Is that deliberate?” she asked.

“Is what?”

“You’re staying within the White Court. Nothing from the Red.”

“I’m afraid I haven’t stayed purely within the White.”

“Oh.”

“But nothing from the Red. That’s true. Other pantheons exist. Foreign clients.”

Another pause emerged, during which a local boy offered to bring them food. Savina paid for two meals, on delivery. As coins and food changed hands a few minutes later, the man fiddled with the beads and muttered an invocation she vaguely recognized as a purification ritual.

“I’m Raicho,” the man said, drawing a thin dagger―a misericorde, designed for thrusting between plates of armor. He speared a chunk of hale ram and ate it off the dagger’s tip.

“Savina,” said Savina. “And I think I might have been followed.”

Raicho nodded, unsurprised. “By?”

“A man. I think. Or several men.”

“Couldn’t see a face?”

“No, I saw faces. A few of them. But… still, all three men seemed to walk the same.”

Raicho didn’t laugh or mock. She’d half expected he would.

“One man, several masks, perhaps,” he mused.

“Maybe.”

“Or three brothers with similar training.”

“Maybe.” Neither of those seemed right, though, and Raicho picked up on her tone.

“Doppelganger?”

She paused. That was closer, but … “I hope not.”

Raicho leaned forward. “Is that him? Upper gallery, over the arch.”

Savina turned and looked up to the second floor over the courtyard. Framed in a sliver of a window was an entirely new face, looking back at her. When she turned back to Raicho, she realized she was holding her breath and slowly exhaled.

“Yes. That’s him.”

Raicho nodded. “You know your lore, yes?”

“I think so.”

“Do you know the poem ‘The Nameless Bridegroom’?”

“Yes.” Pause. “Oh. A nithganga?”

Northern legends described the nithganga, or covet-boge, as a relentless, inhuman stalker, one that always pursued the same prey and never appeared the same way twice. She’d always considered them mythical.

“Maybe,” Raicho said. “Just a guess. Never met one.”

“I suppose I should be grateful,” she said, “that all he’s done so far is watch.”

Raicho laughed.

“What?” Savina asked.

“He poisoned us,” Raicho said, matter-of-factly.

“What?!”

“Well, me. He poisoned me. You haven’t touched your food.”

Raicho speared another piece of hale ram and chewed it. He raised his cup in silent toast to the man in the gallery.

“Are you sure?” she asked.

Raicho nodded.

“That’s what the purification ritual was for,” she said.

Again, a nod.

“And, … it worked? Your, um, spell?”

Raicho gave her a curious look. “Of course it did. Your stew is safe, too, by the way. Might be a bit cold now.”

Savina clenched her teeth. Years of practice with rituals, of careful study, of devout prayer, and faithful service to one god. That’s what she’d put in. She’d never achieved a single magical effect. But the unapologetic infidel across from her was tossing out spells over dinner. And joking about it.

Raicho studied her face as she tamed her annoyance. Then he leaned back and removed a mid-sized Kirin hammer from his belt. He set the hammer, head-down, on the table between them, by his machete. Along the handle of the hammer he had inscribed its name: Grammar.

“Grammar the hammer?” she asked.

“Sure. Seems an appropriate name for something you bludgeon people with.”

“‘With which you bludgeon people,’” she corrected.

“See what I mean?”

“What’s it doing on the table, Raicho?”

“Your pursuer just realized he needs to try another strategy. He’ll try it soon. So I need to ask you a question,” Raicho said.

Savina nodded and took her first bite of the stew, certain that when her anxieties settled, hunger pangs now at bay would flood back in.

“What is the most dangerous thing you’ve ever done?” Raicho asked.

An odd question.

“Probably this,” she admitted. “Coming out here to hire you.”

“That’s why they don’t work,” he said.

“What doesn’t work?”

“Your attempts at magic.”

She stared at him.

“I’ve decided I’ll help you, on one condition,” he said.

“You don’t know yet what I want you to do,” Savina replied.

“That’s not the condition. They tried to kill me and your god backed my spell, so consider me on board. Also, I’m curious.”

“Okay. Then what’s your condition?”

“You have to go through whatever it is, with me. You have to take the same risks.”

“Why?”

“I want to see you cast a spell, Savina. And I’m pretty sure if you risk your life, you’ll cast at least one before the night is through. That’s how it works: You can’t tap into divine power unless you take risks.”

Savina mulled this over.

“I think they’re likely to kill me anyway,” she said.

“Excellent.”

“Okay,” she said. “What do you want me to do?”

“Pick up the hammer,” Raicho said. “Your date is behind you.”

A Defense for the Recusant

Back in October, I first proposed the idea of a cleric who has become a mercenary to the gods, selling his clerical and adventuring services to whichever deity he can bargain with for power.

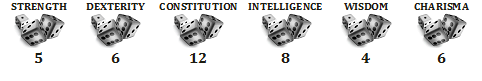

Raicho’s stats as rolled randomly on 3d6, before racial modifications.

Some of my long-time GM friends weren’t quite sure what they thought of this notion. Indeed, a few were more stridently opposed to that idea than they had been for my take on the cleric-as-demigod.

I don’t blame them, really. The standard model for divine physics, for clerics, in fantasy games is You worship a god and the god gives you power — without your god, you are nothing.

Nevertheless, the fine print of that same standard model has fairly consistently supported the following principles, across editions:

- Clerics can switch gods (though it may be messy, and editions vary about the atonements, quests, and other requirements that must be met to fully convert).

- Clerics who switch gods or who fall out of favor with their gods might temporarily lose spell-casting abilities, in part or in whole, but no editions have ever said that they lost levels.

- Divine spellcasters like clerics and paladins don’t have to draw power from a god at all. Instead, they can draw spell power from belief in a widespread philosophy or force, from a multitude of spirits (animism), or from an entire pantheon, rather than from a single member of it. Indeed, the single god model has long been presented as just one option among many. That players and GMs have generally ignored those options is beside the point. (The 5th-edition of the game presents these options in the Dungeon Master’s Guide, pages 11-12, which reproduce almost word-for-word guidance that had already appeared as early as 3rd edition. Note that the paladin has, in 5th edition, completely converted to an alternative model: She still wields powers called “divine,” but all of her powers emerge from the code she adheres to—not from a god.)

- Many members of the clergy, even those with faith, Wisdom, and appropriate alignment, are not spellcasters. (This notion is most recently and clearly repeated in the 5th-edition Player’s Handbook, p. 56.)

- Spellcasting clerics might even, in fact, be seen as troublemakers by church authorities (p. 57).

All five points, taken together, paint an interesting picture: Clerics appear to be special even when not chosen by a single god, echoing something we’ve said before about spellcaster demographics.

Think about it: According to the above points, a 12th-level cleric of, say, Magagara could end her service with that goddess, switching allegiance to the Queen of Masks. After proving herself loyal, she wouldn’t start over with 1st-level spells. She’d pick right back up as a 12th-level cleric of the Queen of Masks, and she’d still cast 6th-level spells! That’s really interesting. Her old ability to handle 6th-level spells appears to have carried over with her. It was part of her, all along.

Suddenly, viewed through that lens, it kind of makes sense that a god would be interested, possibly very interested, in conversions. After all, when Thor converts a priestess of Loki, he doesn’t gain just any cleric—he gains a 12th-level cleric. She’s useful. An asset. (And Loki loses a 12th-level agent at the same time!) Sure, there might be a risk of betrayal, but valuable assets often carry risks, and deities, we might imagine, are probably good at that calculus.

At the same time, a god might have many devoted servants who are wise and can read the rituals, yet many of them never work magic. Now suppose that one of them, a devoted servant for 20 years, finally does start casting spells. One imagines that new cleric would start at 1st level, not at 12th (or 20th). If so, that’s also very interesting. Clearly, years of experience matter more than years of devotion. Again, that’s a trait of the cleric, not the god.

In short, it seems likely that clerics’ ability to channel divine power is innate, and gods use clerics because of this fact. Faith, Wisdom, and alignment may all matter, but there must be a mysterious fourth ingredient that goes into making someone a true cleric, and that power is carried with them wherever they go and whatever they believe. A god might get angry with a wayward servant and send angels to smite her, but when they smite her, she’ll still be a cleric, just as a fallen angel is still an angel. She might temporarily be denied spells, but a cleric she remains. She could atone, switch camps, become an animist, or devote herself to a philosophy, and pick up right where she left off.

So what makes the spellcasting cleric special? Certainly, you could rule that clerics have a special gene or inherited, natural aptitude. However, a fun alternative appears in this excerpt from the 3rd edition Deities & Demigods:

[Divine] power stems not only from worship, but from all sorts of actions. The amount of power generated by such actions is in direct proportion to the effort and sacrifice required by the action. Considering the risk taken and the effort made routinely by adventurers, it’s obvious why they’re important to your deities (p. 16).

That’s a pretty powerful idea for a GM to play with: Clerics can channel divine magic because they take risks in the name of their beliefs, and the more risks they’ve taken as clerics in the past, the more divine power they can channel. I’ve played with that idea in the above narrative. It’s possible Raicho is wrong, of course. Maybe he’s fumbled his Intelligence check. I haven’t decided yet.

If that’s how it works, though, then active adventurers with Wisdom, appropriate alignment, and willingness to serve are valuable pieces on the Divine Chess Board. And if they have past experience channeling divine power (anyone’s), they’re even more valuable—even if maybe they’re also a little unpredictable or hard to trust.

Moreover, if that’s how it works, mercenary clerics who barter their services to whichever god is willing to compensate them may not be popular.

They may not be common.

They may even be short-lived.

But they’re far from impossible.

I’d even say they’re likely. If you like the idea of recusants but don’t want to open the door to free-market chaos in your campaign’s temple district, here’s a potential complication: Raicho thinks he’s independent, but can he be sure of that?

That is, how does Raicho know that the “gods” employing him aren’t all the same tricky, imposter god with a nefarious and unstated plan in mind?

Answer: He doesn’t.

Fear of such tricks might keep many clerics on the straight-and-narrow, and leave most of them suspicious of characters like Raicho.

Understandably. †

♦ Graham Robert Scott writes regularly for Ludus Ludorum when not teaching or writing scholarly stuff. Graham has also written a Dungeon Magazine city adventure titled “Thirds of Purloined Vellum” and a fantasy novella titled Godfathom. Like the Ludus on Facebook to get a heads-up when we publish new content.

PostScript. Some Redditors have correctly pointed out that I didn’t address what happens to Rancho’s domain when he switches employers. Answer: It stays the same — Trickery. A cleric using any of the more official alternatives, like worship of a pantheon or animistic faith, would have a single domain and that one wouldn’t change, so the recusant’s, following precedent, shouldn’t change either. One interpretation of this pattern (which existed in the rules before Raicho) is that the domain reflects the cleric’s nature rather than the god’s. A cleric inclined toward the tempest discipline is likely to pick a storm god, for instance. Another way to look at it is that Raicho is being deceived by a single tricky god into thinking he is more free than he actually is (see commentary above), and that such a god would probably have Trickery as a domain, which is why I gave Raicho that one.

I got a fun Dresden vibe from this. Fantastic story, and very interesting idea for a cleric. I would allow it, it seems reasonable.

Thanks for the feedback, Duncan. It’s encouraging to hear the story worked for you. I haven’t read Dresden, I’m afraid, though I know what it is and am fond of the FATE system. But if it’s similar to the kind of stuff I like to write, maybe I should read some of Butcher’s stuff!