Get Medieval: Medieval Ruins

When we think of ruins from our modern perspective, we often think of the relics of the medieval world. Decaying castles, ruined monasteries, and the remnants of city walls feature prominently in our pantheon of ruins, and it’s no wonder: Those images are aesthetically pleasing and evocative. Ironically, though we often associate the medieval world with ruins, the landscape of much of the western medieval world was itself liberally sprinkled with ruins of even more ancient ages that were equally evocative to the medieval mind.

To be sure, plenty of castles had been destroyed by siege. Villages or even towns often were left fallow after plagues. However, much of what the medieval traveler would have identified as ruins would have come from even more ancient sources and could have had a very different set of connotations.

“Hubert Robert – View of Ripetta – WGA19603” by Hubert Robert – Web Gallery of Art: Image Info about artwork. Licensed under Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Hubert_Robert_-_View_of_Ripetta_-_WGA19603.jpg#/media/File:Hubert_Robert_-_View_of_Ripetta_-_WGA19603.jpg

History & Myth-Making

Image showing Merlin directing the building of Stonehenge by a giant.

From the Roman de Brut by Wace, from the Manuscript Egerton 3028 in the British Library.

This is a faithful photographic reproduction of a two-dimensional, public domain work of art.

The ruins of past civilizations are often re-appropriated by their inheritors, and just as often reinterpreted to fit with the inheritors’ cosmology and theology. When introducing ruins in a fantasy role-playing game, it can be useful to think about both the real and the imagined histories associated with the monument.

Ruins provide an opportunity to supply useful back-story for your campaign world without resorting to exposition or handouts. Describe the broken statues of ancient kings. Let PCs read (or decipher) the remaining inscriptions. These details can immerse players in the lore of your world in a manner that doesn’t bore them to death. Meanwhile, the stories the locals tell about the ruins can provide a mix of useful information and misleading folklore. These tales may mix history and legend together in a fashion that reveals more about the tellers’ beliefs and suppositions than it does about the ruins — but even those cultural insights can be useful or interesting! Of course, in fantasy role-playing the line between history and myth can be quite blurry, but then again, such was also the case in the Middle Ages.

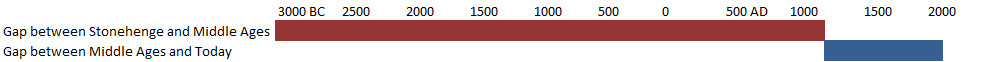

The impressive stone monuments of ancient cultures were to be found in nearly every corner of medieval Western Europe. The imposing Neolithic and Bronze Age stone circles, of which Stonehenge is the best known, may date as far back as 3000 B.C. — though the Bluestones and the enormous Sarsen stones of the henge weren’t erected for another 400 to 500 years — making them at least four times as old from the perspective of their medieval admirers as the medieval ruins are from our own contemporary perspective!

Not surprisingly, these impressive monuments evoked all sorts of myth-making and creative responses. Stonehenge, for instance, is attributed to the magic of Merlin or to the labors of giants – or even to a combination of their efforts – as described in Monmouth’s Historia Regum Britanniae and in the Roman de Brut by Wace. Incidentally, that later text also explicitly links the founding of England to the Trojan War and thus to the founding of Rome.

Of course, the Roman ruins would have to figure prominently in any discussion of what the medieval mind would have acknowledged as ruins. It is hard to comprehend the sheer scale of Roman ruins throughout continental Europe or how pervasive and prevalent they were. The Romans built on a grand scale and they tended to build quite well. Just think how many monuments of their culture are still standing thousands of years after their construction. Educated folk of the medieval period were quite aware of the history of the Roman Empire and recognized many of the Roman ruins for what they actually were. Still, during the Dark Ages, as nomadic groups of barbarians repeatedly swept through regions previously held by the Romans, the original context of such monuments could be lost. It’s easy to see how those early invaders came to attribute the massive stone structures they found to the work of giants and to ascribe the delicately crafted jewelry and mosaics to the artifice of dwarves.

Of course, in a fantasy world it is entirely possible that giants and dwarves did build those artifacts. Yet, it might be interesting to think about how even such fantastic origins might be re-imagined and re-appropriated by new generations and developing civilizations. Just because the origins of a ruin are fantastic doesn’t mean they can’t be made even more spectacular and mythic by those who speculate about them generations later, through the dust and cobwebs of time.

Ruins that Aren’t

One point to keep in mind is that most ruins were not generally isolated or off in the wilderness. The Romans built where people congregated, and the vast majority of their construction projects were for civic purposes. They built streets, roads, markets, and aqueducts, and those features continued to be used and to play a vital role in the societies and cultures that followed.

This may be one of the most important historical notes to keep in mind about ruins in the Middle Ages: They continued to be used.

Indeed, many cities of the Middle Ages were built on the remains of Roman fortifications or urban centers. The foundations of buildings, the layout of the streets and even the sewers beneath them may have been of Roman vintage. It was not at all uncommon for layers of habitation to accrue, one above the other, particularly in urban centers, and for the “ruins” to be put to good and practical use. The cellar of a merchant’s house might have been built by Roman hands and even have carvings dating from the days of the empire. The town fountain might be a thousand years old and still carry water from an aqueduct with a source miles away in the hills. The roads used everyday might still be paved with Roman stones, and would almost certainly follow the lines laid out by surveyors a thousand years in their graves.

This means the PCs — as happened in one of our own memorable campaigns — might purchase property in a city only to find that behind the walls and beneath the surface, the property has unusual, forgotten origins. In a truly historic city, set in a fantasy realm with its constant threats and epic treasures, you really can adventure in your own back yard.

Ruins might also be encountered in another unexpected location, in new construction. An important point to remember is that there was not the same sense of respect for ruins that we now take for granted, or at least that most of us do. Aside from simply using or building on top of preexisting ruins, medieval builders would regularly reuse classical building materials in contemporary structures. Large ruins might even function like a quarry for newer building projects, with masons carting off whole chunks of precut stone from ancient ruins to use in raising new castles or cathedrals. If the pieces already had finished decorative elements, then so much the better – as long as they weren’t too obviously pagan.

It’s actually quite shocking to realize the degree to which this practice occurred and was even authorized by the establishment. No less an institution than the Vatican made a tidy profit selling off chunks of the forum ruins until Pope Paul II ended the practice in the fifteenth century and reinstituted the death penalty for destroying the monuments. Here is a wonderfully evocative quote from Daniel Boorstein’s The Discoverers that provides a great sense of the scale of ruin re-use in the Middle Ages.

Roman roofing tiles in the wall of St Nicolas chapel.

Credit: Bureau Archaeology and Monuments, City of Nijmegen

The thin slabs of ancient epitaphs were easily adapted into borders and panels or fitted into pavements, which explains why the floors of Romans churches are so richly and irrelevantly inscribed. It is easier to pry a block from a crumbling ruin or dig it out of the Roman earth than to quarry it fresh from the hills of Carrara. Across Italy the competitive ambitions of rising medieval towns created a demand for new churches that seemed endless. Duomos and campaniles needed heavy stone foundations, thick walls, and monumental arches.

As the industry grew, and as the Romans marble cutters’ booty exceeded the needs of the local market, they shipped more and more of their wares abroad on light coasting ships for the new cathedrals of Pisa, Lucca, Salerno, Orvieto and Amalfi, among others. Pieces of Roman marble can be identified in Charlemagne’s cathedral at Aix-la-Chapelle, in Westminster Abbey, and in churches in Constantinople.

(p. 581 The Discoverers, Daniel J. Boorstein, 1985)

Though tragic in the real world, such architectural cannibalism can be a wonderful inspiration for fantasy role-playing games. A recently fortified castle might be made with stones from a nearby ruin — and those borrowed stones might have decidedly nasty and unexpected properties. Think of how many American movies, set in a nation with a much shorter history, involve ill-advised building on Indian burial grounds. That trope is, in fact, far more appropriate to a fantasy campaign in which someone might be reusing stones from the ancient temples of an aquatic or subterranean master psionic race. Similarly, a pillar with an ancient inscription in an arcane language, providing clues to a treasure trove, might be incorporated into the new temple of a church where no one has any idea of its potential value or significance. If nothing else, just using these wayward architectural pieces for evocative descriptions can be inspiring and allow you to represent the pageant of history and the fall and rise of empires in physical form.

How Ruins Got Ruined

Every ruin your PCs see had to get… well, ruined. Their prefigured destruction provides another pathway to develop the history of your game world. History tends to be punctuated by periods of intense devastation that might create a significant number of ruins in short order. Often the abandonment and destruction of such expensive and monumental structures was part of some larger significant and traumatic historical event. Again, describing a bit about the damage to a ruin and uncovering some of the history of its fall into decrepitude can help you reveal the history and major events of your game world without resorting to those dreaded expositions.

Let’s return to the most evocative ruins produced by the Middle Ages themselves — and focus on the example of England, which has a rich history of such ruins.

We can pinpoint two specific events that had a profound effect on the monumental architecture of England, most notably on the monastery and castle ruins that dot the countryside. The Dissolution of the Monasteries conducted by Herny VIII between 1536 and 1541 resulted in the destruction of hundreds of religious estates. Their movable property was appropriated and their lands divided up. Many of these impressive structures that housed friars, monks, and nuns fell into disuse and ruin. A large number of these ruined abbeys can still be seen throughout England, inspiring poets, artists and tourists for generations. All hearken back to the English secession from the Catholic Church and the religious strife of the 16th century, providing a physical reminder of the tumultuous history of that period. Similarly, ruins in your realms might result from religious struggles in a population.

The monasteries of England went out with a bit of whimper, but many of the ruined castles that grace Wales, Yorkshire, and the Midlands went with a bang. The use of gunpowder and explosives in the destruction of many of the castles that were slighted (the technical term for the intentional destruction of a castle – love those obscure terms) during the English Civil War has probably been exaggerated. (Yes, American readers: England has had Civil Wars. Game of Thrones is inspired by one of them.) However, a large number of castles in England were destroyed toward the end of the war in 1651 by the Parliamentary forces to prevent their use by loyalist Royalist holdouts. Most famously, Pontefract Castle, which changed hands repeatedly during the prolonged conflict and managed to hold out for Charles even several months after he was executed, was slighted at the request of the local population. They were likely pressured by Parliament to request the destruction of what was arguably the strongest fortress in England, but they no doubt were glad to see the end of a structure that had concentrated so much fighting in the local region. A similar fate befell many castles during this period, even though –ironically – their military usefulness was already starting to wane as more effective artillery developed.

Both of these historical events, each leading to the destruction of so many great medieval monuments of England, took place significantly after the actual Middle Ages themselves. Indeed, perhaps the greatest destruction of medieval architecture occurred within living memory as a result of the catastrophic bombing that took place in World War II. Similar but more tropically appropriate events could have wreaked havoc on the ancient architecture of your fantasy gaming world and have left their own traces in the burnt-out shells of castles, towers, keeps, and temples. Each of these periods of destruction tells a particular story of struggle and conflict that would significantly impact the course of history and the nation. The ruins in your game should be equally rich in history, and the stones should speak volumes.

Wondrous is this wall-stone, broken by fate,

the city burst apart, the giant-work crumbled.

Roofs are ruined, towers ruined,

rafters ripped away, hoarfrost on lime,

gaps in the storm-shelter, sheared and cut away

under-eaten by age. The earth grip holds

the mighty makers, decayed and lost to time

held in the hard-gripping ground while a hundred generations

of people watched, then died. Often this wall waited,

lichen gray and red-stained, through one kingdom after another,

stood against storms until steep, deep, it failed.

Verse Translation from Anglo-Saxon of “The Ruin” from the 8th Century Book of Exeter

Possibly referring to the city of Bath in England

By Miller Oberman, from the Old English Poetry Project

https://web.archive.org/web/20150402074418/http://oepoetryproject.org/the-ruin-millers-translation/

Click here to read our other recent article on design principles for ruins as adventure areas.

![Carl Gustav Carus [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://ludusludorum.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/Carl_Gustav_Carus_-_Tintern_Abbey-1024x680.jpg)