Get Medieval: What Were the Middle Ages?

“Now father, you’re living in the past. This is the fourteenth century. Nowadays …”

– Walt Disney animated feature Sleeping Beauty (1959)

A Franco-Scottish force led by Jean de Vienne attacks Wark Castle in 1385, from an edition of Froissart’s Chronicles.

This image (or other media file) is in the public domain because its copyright has expired.

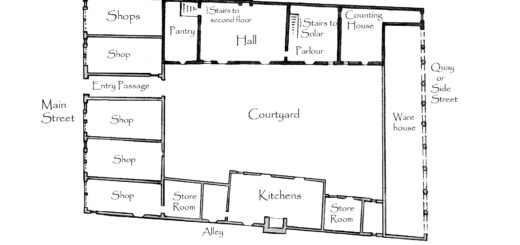

The “Get Medieval” series of articles we have been releasing are designed to give some useful perspective on what the real Middle Ages in Europe–that fascinating period of history so closely associated with the majority of fantasy role playing games–were like, and what interesting facts, information and inspiration we can take from the medieval period. So far I’ve written about the medieval village, the most common inhabited setting that would regularly be encountered in a game world, and the medieval town, introducing some of the more interesting and less obvious features of the medieval urban experience. I’m currently working on wrapping up this trio with an article on cities, the rare but incredibly significant metropolises of the medieval world.

However, I’ve recently realized that, while working on this series and also mentioning the medieval period extensively in some of my other articles on the site (such as my discussion of why D&D really isn’t all that medieval – I see the irony as well!), I’ve never really defined what the middle ages actually were as a historical period. You can certainly find that information elsewhere (the Wikipedia article on the Middle Ages is actually quite good if you want a lot more detail), but I wanted to put forward a brief description of the three main stages of medieval history and consider how they might relate to different types of fantasy game world settings.

Often when people talk about a fantasy setting as being “medieval,” they presuppose a singular culture, unchanging and universal. However, there was actually quite a bit of variety over the period, which stretched from the somewhat ambiguous fall of the Roman Empire to perhaps the Reformation (roughly between 300 and 1500 AD). More than 1200 years of history are contained by what we call the “Middle Ages.” That’s more than double the time between its “end” and our present time.

A future article in this series will focus on technological innovations in the period, but for now it might be useful to describe the three periods into which the Middle Ages are typically divided: the traditional “Dark Ages” (300-1050), High Middle Ages (1050-1300), and the Latter Middle Ages (1300-1500). Those dates are a bit loose and different regions of Europe “evolved” at different rates, but they serve well enough as benchmarks. My dates are a bit Anglocentric, for instance. Following are brief descriptions of each of the main periods and some notes on the kinds of settings that might best draw inspiration from each.

The Dark Ages (300-1050) were indeed something of a blot on the idea of uninterrupted historical progress. Following the dissolution of the Roman Empire in the west, a series of barbarian migrations displaced much of the sophisticated culture of late antiquity and left in its place a collection of slowly coalescing kingdoms. However, this period also saw the unification of Europe under the Catholic hegemony that held together the remnants of Roman civilization, as well as a surprising number of technological and social developments. Many of the broader European cultures that we still recognize coalesced in this period.

For this period, think of Beowulf, invading barbarians and Vikings. The Dark Ages is a great source of inspiration for games with a more primitive and barbaric feel, or for games taking place after the fall of some once mighty empire.

The High Middle Ages (1050-1300) saw the recovery and expansion of trade and urban life. Many of the commercial developments (such as banking, credit, stock, and companies) that we now take for granted were initiated in this period. The nation-states of England and France also saw their genesis in the latter potions of this age, and both the political and military institutions needed for their continued operation were inaugurated. This period also saw the expansion of traditional horizons as trade and the crusades brought new realms within the sphere of Europe. Religious devotion and a strong papal monarchy encouraged fantastic architectural feats, such as the cathedrals, and also established a powerful (though not entirely unquestioned) cultural hegemony.

For the High Middle Ages, think of Ivanhoe, chainmail clad crusaders, castles, keeps, and cathedrals. This period is perhaps the most iconically medieval, and is great inspiration for a maturing feudal society with all the traditional chivalric trimmings.

During the Latter Middle Ages (1300-1500), vernacular languages arose, traditional feudalism began to dissolve, and powerful monarchies ascended. The growth of trade continued, and merchants gained in status and power throughout Europe as the aristocracy and the Church lost their stranglehold on the reins of government. Climate change and The Black Death led to a radical decline in population, which somewhat paradoxically raised the value of labor and provided for a dramatic increase in the standard of living for many peasant families. Intellectual culture began to rediscover the works of antiquity, daring to add to the artistic and scientific accomplishments of the past, and even to question the authority of the church.

For the Latter Middle Ages, think of The White Company, knights clad in full-plate at tourney, English longbow-men in the field, the Plague, and the peasant’s revolt. This period has the full range of military and social features so essential to our conception of the medieval along with the dynamic complications of changing economic, technological and political developments. It’s a great source of inspiration for games with a bit of an edge and with some more modern features.

In my own “Getting Medieval” series of articles, I have generally focused on the end of the thirteenth century with some consideration of the mid- to late-fourteenth Century. The turn of the thirteenth century to the year 1300 marked something of a “Peak” in the medieval era, and I often refer to this period for inspiration on what maximum population, trade, and production could look like in a medieval society.

After 1300, the Little Ice Age and the Plague essentially halved the population of Europe, ushering in a season of instability and dynamic change. This was the time of the Hundred Years War between England and France, and it saw the coming of the Plague with all of its attendant social upheavals. This is also the age of Chaucer, the Pearl Poet, Dante, and the growth of urban London. It is a time when the medieval truly met the modern, and as such it is able to inspire the nostalgia that seems part and parcel of the fantasy experience, while being familiar enough for the layman to grasp. However, in future articles I will also discuss other periods of medieval history and focus on how they can be equally inspirational. I hope that readers will share my appreciation for this period of history, and explore with me the many ways that the real medieval can add to the fantasy worlds we love and cherish.

“So they lived, these men, in their own lusty, cheery fashion–rude and rough, but honest, kindly and true. Let us thank God if we have outgrown their vices. Let us pray to God that we may ever hold their virtues. The sky may darken, and the clouds may gather, and again the day may come when Britain may have sore need of her children, on whatever shore of the sea they be found. Shall they not muster at her call?”

– The White Company, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (1891)

Really handy stuff. I think it gives a positively solid foundation to work from for anyone.

Thanks Flannel, and there is much more to come! I’m particularly glad you found it approachable. I love the middle ages and how much depth and and inspiration there is in the history and culture of the period, but it can be overwhelming. There are (at least) 1200 years of history there!