Get Medieval: The Town in the Middle Ages

This is the second installment in the “Get Medieval” series, exploring the historical world of the Middle Ages in Europe, particularly in the 13th and 14th centuries in England, as a potential source for inspiration in D&D and other fantasy role-playing games.

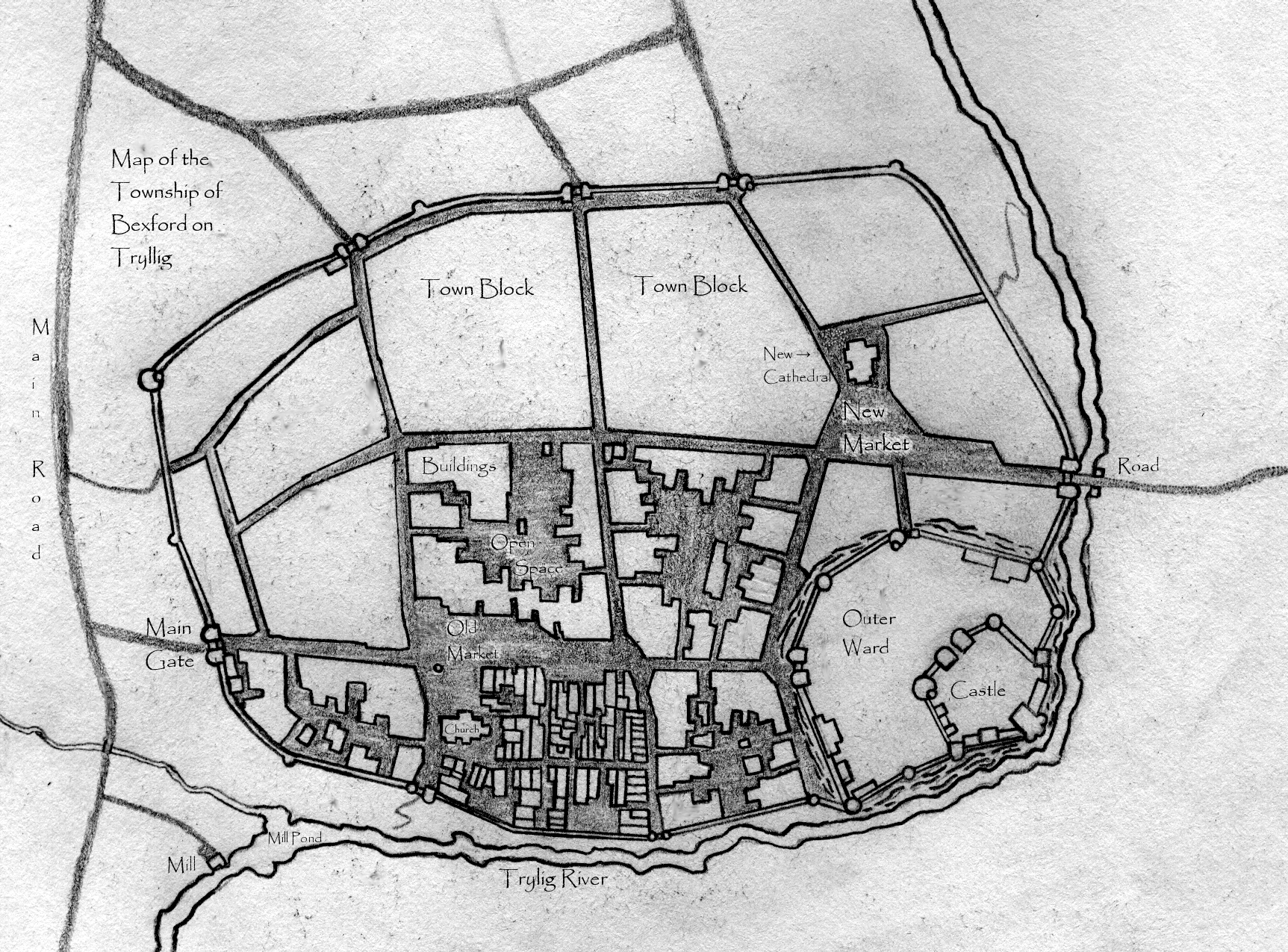

Map of Bexford on Trylig: Bexford on Trylig is town of some four thousand souls, putting it right in the middle range for the countryside towns in terms of population. It is located on a tributary of the Rin and is thus not on any major trade routes. Bexford lies at a ford (now a bridge as well) crossing the Trylig river which runs down from the Dragon Wall Mountains. It also owes its modest prosperity to a junction of roads and is two to three days travel from several larger settlements. It does not lie along the main Causeway, but the increased volume of trade with settlements established or rediscovered since the Dwindling in recent years have helped create a booming economy in the region.

The 13th and early 14th centuries in England saw the rapid development of new urban centers, and the dramatic expansion of the few pre-existing centers of trade. By the year 1300 around 10% to 15% of England’s population lived in an urban environment (some estimates go higher, but are problematic), and there were as many as 75 towns and cities that could boast a population over 2,000. Only a few of these centers for manufacture and trade were true cities, London may have held as many as 80,000 souls, Norwich probably boasted a population around 25,000, and a few other settlements like York had slightly in excess of 10,000 citizens. The vast majority of urban dwellers lived in the 20 or so major towns with populations of between 5,000 and 10,000, or the more than 50 centers with 2,000 to 5,000 inhabitants.

The line between town and city is not entirely clear and could vary regionally and culturally. For the purpose of distinguishing the village from the town and the town from the city, we will rather arbitrarily designate any settlement with less than 1,000 denizens a village, any settlement with between 1,000 and 10,000 a town and any center with a population greater than 10,000 as a city. True cities with tens of thousands of inhabitants were quite rare and had their own distinct features and characteristics (and will be dealt with in a future article in this series), but larger towns with 12,000 to 15,000 people were really just larger versions of the standard towns. Most true towns in the late medieval period generally had a population of between 2,000 and 8,000, averaging toward the lower end of that array at around 2,500 to 3,000 citizens. This range seemed to be a functional population for local urban centers.

| See the previous article in this series, on the medieval village. Other related features include our sample village of Mistmill and our population engine, which challenges some of the base assumptions many generators use, permits you to adjust settings, and produces non-random results based on the settings you’ve provided. |

There were actually even more small or “Market” towns scattered around the countryside, usually with a population of between 500 and 2,000 souls. However, they generally lacked a mercantile population of any significance and were almost entirely local centers of trade. They were not really towns in the conventional sense of how we imagine urban centers, though they could have some skilled craftsmen and a semblance of town government. These smaller towns were the common experience of the vast majority of the population; few people lived more than a day’s journey from such a place and would likely have been there to market or for festivals on a fairly frequent basis. These market towns were a sort of hybrid between the agricultural village and the urban world.

The Physical Environment

All of these towns had several distinctive characteristics that set them apart from the villages of the surrounding countryside that were home to the vast majority of the population. (See the previous Get Medieval article.) The most important distinguishing characteristics were their size and the density of settlement within them. The average country village only had between 200 and 500 inhabitants, and these were spread out on plots of land with plenty of space for outbuildings and personal gardens. In the towns, people lived in plots called burgages which ran from about a quarter to a half an acre. In time these plots were further subdivided until the population density at the center of major metropolitan centers could reach over 90 people an acre (greater than that in most modern cities), although a figure of about 50 an acre was more usual.

Competition for valuable space along the commercial thoroughfares was even more fierce than was competition for living space. Shop frontage was quite valuable, and many shops would have to make do with a space only 7 feet in width for displaying goods. The limited space and the fact that many craftsmen worked on and sold their goods at one and the same location determined the traditional form these shops took. Most of the wall adjacent to the street was taken up by a double, vertical shutter, with each half opening a different direction: down to form a display table for goods, and up to form an awning to protect goods and customers from the elements. Doors were kept small, and there was no need for the customer to actually enter the shop; they would simply look at the goods on display and bargain with the craftsman who worked his trade behind the counter while he waited for customers.

This diagram shows a typical burgage plot with shop fronts along the main street and a hall and courtyard. This plan is fairly typical example of right angle (because the hall is at a right angle to the street frontage) courtyard design, with the addition of a second set of inner buildings parallel to the main hall and a warehouse at the back, thus fully enclosing the compound. The entire structure would likely be owned by a wealthy merchant who might also use the shops, but would be more likely to rent them out. There might also be another floor (or two) above the ground floor shops, serving as residences for the craftsmen who worked on and sold their wares below. This would certainly be the case in the main buildings associated with the hall. The diagram is based upon the still preserved medieval building known as Hampton Court in King’s Lynn.

Because street space was so valuable, people often lived above their shops, and medieval buildings in densely settled cities could rise four or more stories above the street. In addition most would have some kind of cellar which might also serve as a kind of double shop frontage, providing a row of shops along a recessed patio above ground, and a gallery of businesses below. The town of Chester in England has a beautifully restored example of this kind of structure called The Rows. The upper stories of buildings also tended to encroach on the space below them, hanging out over lower levels on the street. This could reach ridiculous lengths in some towns where the upper stories actually jutted out to cover more than half the street below, or (as can still be seen at York in a section known as The Shambles) where the upper floors on either side of the street came close enough together in the middle for the tenants on either side to reach out the window and shake hands. Such conditions had obvious repercussions on the environment, blocking out sunlight and making it very easy for the frequent and deadly fires that plagued medieval urban centers to spread.

Many towns were built upon pre-existing Roman settlements and incorporated defensive elements from these ancient structures. The grid street plan common to Roman civic engineering also influenced the layout of many medieval English towns. Commonly a town had from two to four major gates at which traffic into and out of its precincts could be controlled, and which also influenced the general layout of its thoroughfares and by-ways. Later defensive structures, such as castles for the local lord or the crown, might be integrated with the town’s defenses. Monastic houses or governmental structures could also influence the layout of the community, taking up large portions of the urban region.

The center of the town was usually to be found at the junction of the two largest streets that ran through it. Often a large portion of the property surrounding such a crossroads would be left open for markets, fairs and public events. Sometimes the stalls that had originally been set up around such fairs became over time permanent structures, thus colonizing the public territory of a developing town. The town church or cathedral was also likely to be located adjacent to the marketplace, as were important civic buildings such as the courts of law or a lord’s dwelling (in the case of privately held towns). The property along the two main streets was the most densely settled area of the town and the focus for much of the community’s mercantile activity. England was blessed with relatively little internal turmoil for much of the period that witnessed the flourishing of these regional centers and so the development of its towns was less influenced by purely military concerns. Many towns had large suburban areas extending beyond the walls along the main roads. Still, the walls served to focus and limit the development of towns in a world where catastrophic physical violence was always an all-too-real possibility.

Even among such built-up surroundings, the country was never as far away from the town as it is in many modern urban centers. Though the main thoroughfares were densely peopled, there was often still more open space within the town than developed buildings. The narrow frontages mentioned above gave way to long strips of land stretching out behind the main streets that could provide secondary housing, work space, or even gardens and room for livestock. Many people within even the highly developed precincts of London kept sizable vegetable gardens behind their shops. Chickens, pigs, and even cows were kept within the cities and towns, often in substantial numbers.

Town and Country

The ties to the countryside were strengthened by constant contact with the denizens of the nearby villages and farming communities. People came to the towns for markets and to buy goods not available from non-professional craftsmen, and many of those who lived within the town (at least among the smaller enclaves) worked the fields around it. Even more important was the constant stream of immigrants from the villages to the towns. More than 70% of a town’s inhabitants were likely to have been born outside its precincts. Inside the close quarters of the urban centers, disease took an unusually high toll on the citizens. Although statutes to regulate garbage dumping, fire hazard and other such threats to public safety were increasingly successful throughout the period, the fact nevertheless remained that, especially for the urban poor, a lower than average life span was the rule.

Yet there were still enough advantages to town life to attract these new comers. Foremost among these must have been the freedom conveyed by living within a town. As mentioned in a previous article about the medieval village, many peasants were tied to the land they worked. Their freedom to move was severely curtailed and they owed sometimes crushing work services to their local lord. Living in a town for a year and a day traditionally (and legally) made a peasant free from such burdens. These freedoms were necessary for the development of a mercantile economy, and towns acted as a sort of capitalist enclave within the larger feudal or manorial economic structures.

This is not to say that the towns themselves stood outside the feudal and manorial cosmos. Most towns were “owned” either by the king or some other lay or ecclesiastical overlord. Rents were paid for the right to live on the burgage plots (though these later became relatively fixed and thus almost worthless), and the community as a whole was required to pay a set “farm” fee to their feudal overlord. The king and some other powerful lords also had the right to levy taxes on their towns and to extract a number of fees and dues from the town, its markets, bridges, mills, and other traditional sources of siegnurial income.

Town Demographics and Politics

Working for the town (though often to the benefit of the lord as well) was the town’s own guild, an organization usually comprising all property owners within the settlement. Though similar to trade guilds, the town guild is not like the other guilds you may more frequently hear or read about. (The actual word at the time was “gild” – or even earlier “ghilde” – but in modern and particularly American usage it is spelled with the “u” and I have followed that convention here.) These “Guilds Merchant” as they were called had several functions, including the regulation of markets and the promulgation of rules and legislation regulating trade, as well as the authority to uphold such rules in their own court. In addition, these communes of the citizenry of the town would bargain with the lord of the town, paying lump sums to spare themselves from unwanted tolls, to buy freedom from market dues, and even to collect the town’s annual “farm” payment. Those wishing to become a member of the community might have to pay entrance dues, and the town guild could levy dues or force loans in order to get the necessary income to pursue their projects.

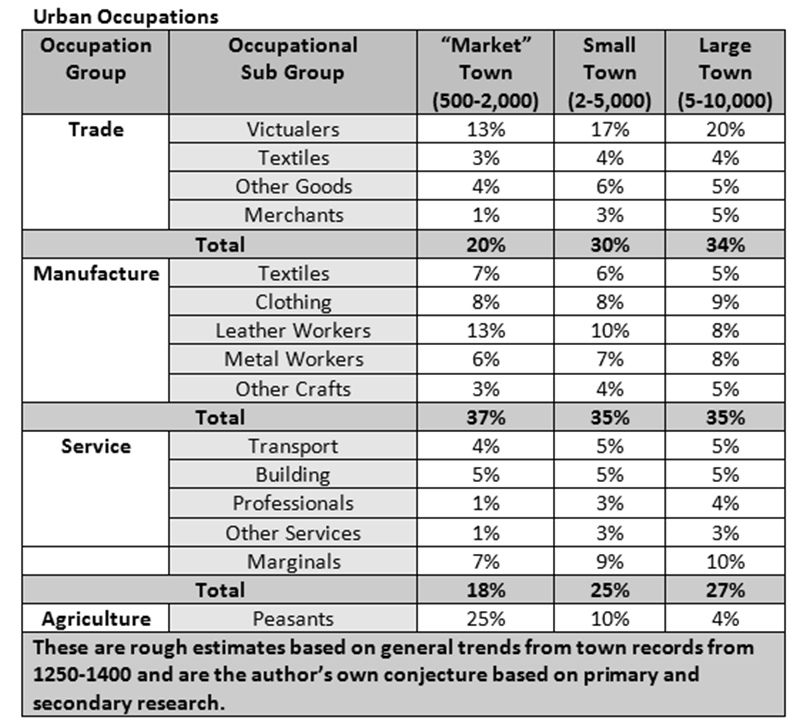

These were not the only guilds in the towns of course, and most gamers will be at least cursorily familiar with the idea of crafts guilds and merchant associations. While these were not at all universally present, guilds were an important factor of life for both craftsmen and merchants. These two groups were the most prevalent social forces in most towns, but they were not the only divisions. Together, merchants and craftsmen comprised a slight minority in most towns. Most towns would also have a varying number of denizens who were engaged in service industries or who worked as wage laborers. Somewhat surprisingly, towns might even have small numbers of peasants.

Peasants: Country in the Town

Smaller and especially “market” towns might have significant numbers of agricultural workers tending fields outside of the town’s limits but living within its protective precincts. The larger the town, the smaller the proportion of the population that would be involved more or less exclusively in agriculture. In any case, their numbers would never be more than a few hundred, about the number of peasants found in a large village. Many townsfolk had garden plots behind their homes, but the vast majority of food came from nearby fields and villages. Many towns would also be surrounded by a close network of villages, some owned by local lords and others by merchant families with pretensions towards gentrification. The peasants of these satellite villages might exist in a kind of “suburban” state, often laboring in the town for extra coin and thus dividing their professional life between the town and the village.

Service Industries: The Wage Earners

At the bottom of the town hierarchy proper were the service industries, which only represented about a tenth of the population in smaller settlements, but who could make up a third to nearly half of the population in moderate to large towns (those with a population of several thousand inhabitants). This was a diverse group whose members were often counted among the poorest of the town’s denizens. Some professionals, such as lawyers or clerks, might be quite well off, but domestic staff and the inevitable throng of semiskilled laborers who hauled or moved goods from one place to another lived at a near-subsistence level. On notable group of wage earners for whom good records were kept were those in the building trades. These skilled laborers could make a decent living and were vital to the town, literally creating its physical structure. They could make up around 5% of the urban population in towns and cities and formed a sort of solid working class in many urban centers.

The picture grows more complicated when one considers that many journeymen could be employed by craftsmen and would often be paid wages. It is really a matter of personal opinion about whether to consider this group as members of the wage earning service industry or to place them with the craftsman class they might eventually aspire to belong to. It is also worth considering the more marginal portions of the population, ranging from prostitutes (about whom there is some surprisingly good data as they often fell afoul of the law), criminals, vagabonds and the chronically destitute. This group might form a sort of underclass in many towns and could range from a very small number to up to 20% of the population in times of economic crisis or turmoil.

Craftsmen: Makers and Sellers

Craftsmen and manufacturers of goods made up from a third to half of the town’s population. The relative number of craftsmen in a town tended to increase in smaller urban centers and decrease in the larger settlements. Not all crafts were represented by guilds, but where they were so represented, the guilds regulated prices, working hours, and the number of apprentices and journeymen a member could take on. They also enforced strict quality control. Beyond these practical concerns, guilds often served a religious function and were dedicated to a patron saint and the preservation of a shrine. Guilds would additionally serve a charitable function, taking care of members who fell on hard times, giving alms to the poor, and even running hospitals. They might also participate in such civic events as pageants and mystery plays (so named because the crafts guilds were alternately called “mysteries” for the secrets of their trades) where the guild would provide actors to display a scene from the Bible or related material.

It is important to remember that many craftsmen were also retailers, selling their goods from their workshops. Their home, place of manufacture, and place of business were quite likely to be one in the same. Additionally, many crafts and trades were family business with skills and materials passed on through generations. Apprenticeship could be alternately informal or highly contractual. Starting in a craft, an apprentice would become a journeyman as he (or she – women could become members of some guilds) progressed in skills and might eventually have the opportunity to produce a masterwork and thus gain entry in to the craft guild. This could be a relatively routine progression or an arduous process depending on many local and circumstantial factors such as sponsorship, talent and the simple economic realities of whether masters could afford to allow for more competition. As noted above, journeymen existed in a kind of liminal space between the service industries and the crafts, sometimes selling their labor instead of goods.

Merchants: The Town Elite

Besides the craft guilds there were the mercantile guilds, which represented the interests of those who distributed rather than created goods. The numbers of townspeople associated with trade and of those associated with manufacture were roughly equivalent, though craftsmen would likely be just slightly more common. Still, the traders and merchants were likely to be the wealthiest and most influential members of the community. By far the most significant portion of individuals involved in these activities were the victualers, who sold foodstuffs within the confines of the town. They could make up as much as 25% of the population of some towns, particularly in larger and more specialized urban centers. These included butchers, bakers, grocers and others who might add value to their product along the way. The majority of merchants were of this variety, and might be labeled as “Local Merchants,” buying and selling more common goods within the region.

Merchants who dealt in large-scale trade or in specialized goods, sometimes referred to as the “Great Merchants,” worked as middlemen in transporting raw and finished materials from one point to another. These individuals made up the town elite. They could make substantial wealth for themselves that rivaled the riches of the aristocratic lords of whom they were tenants. They often also served as mayors and aldermen for the town, running its government, setting policy, and standing in judgment over their peers.

Politics

Town government developed slowly and erratically, but several common features emerged over time. Central to some degree of self-governance was the town charter, though by no means all settlements had such a document. If a town did gain a charter either at its inception or through some later dealing with its overlord, the document set out the town’s liberties, its rights, its customary laws and its obligations. As mentioned above, the Guilds Merchant or the governing body of citizens of the town would attempt over time to expand their liberties in the charter, and to promulgate and enforce new laws as they became necessary. Civil courts were thus given jurisdiction over matters of finance and trade, as well as local issues that did not require appeal to the higher (royal) courts. The “farm” payment collected by the town’s lord also became a matter for the local government. Originally it had been collected by the sheriff through the local reeve, but as time went on towns won the right to appoint their own bailiffs to collect such taxes, thus giving them more control over their own finances.

Towns in the Vault: The Basin Kingdoms

The urban experience in much of the Vault, and particularly in the region of the Basin Kingdoms, has (at least to some degree) more in common with that of the large Italian metropolis than it does with the more diversified and spread out system of English towns.

A larger portion of the overall population (a little more than 15% of the Basin Kingdoms’ population) lives in urban settlements than did that of medieval England. The Basin Kingdoms boast at least four large cities (Mor Ithel, Mor Gilos and Fleet Arcis and Fleet Prasis) of the size equal to or even greater than that of London in the medieval period, along with several other substantial urban centers. While still small by modern standards, these true cities are distinct from the towns that made up the English urban movement (and will be dealt with in a future article in this series in more detail). However, the numerous small towns scattered throughout the Basin Kingdoms are quite similar in characteristics to the average medieval English town.

The intense urbanization of the major cities has rubbed off to some extent on these towns, networking them more directly with larger commercial ventures and granting them access to more advanced concepts of municipal identity. Almost all towns hold a charter, and many are directly owned by the highest local ruling authority. Curiously a few of the larger cities are in the hands of private lords, the most notable examples being Mor Eston, Weshing and Arshmurga. A number of more recent towns pioneered by grants from enterprising lords are also in siegnurial as opposed to royal hands. The same necessary concept of tenurial freedom by virtue of inhabiting a town that was a critical element of English urban status holds true in the Basin Kingdoms, though villeinage is generally less common than it was in late medieval England. Additionally legal codes are more highly refined and developed as a result of more progressive values held by the Moric Houses that make up much of the Aristocracy.

Town government and guild structures are also highly developed in the regions nearest the central Rin River holdings and in the older towns. However, town and guild structures are occasionally repressed in newer settlements further from the river and the Causeway. Several large merchant associations have also emerged, based upon the immensely successful model of Hydra House: a powerful merchant-family-cum-corporation that is an offshoot of the Hydragyr family. Such associations have contacts in all the major centers of trade. The development of this sophisticated trade network has somewhat increased the power of the merchant class in the region. The availability of capital from the great merchant houses has also enhanced the commercial development of the Basin Kingdoms beyond that of England in the 14th century. (The great merchant houses are also permitted to lend at high rates, unlike their European analogues who labored under religiously motivated anti-usury laws.)

Still, most of the towns in the Basin Kingdoms maintain strong ties to the agrarian countryside, remaining very local and provincial in their attitudes. The Dwindling and the subsequent collapse of central authority over the last twenty years have caused more of them to defend themselves with walls, garrisoning and training militias. This trend is also supported by muster requirements included in the town charters as a matter of course in times of war. Many towns provide a mixed force composed of a small number of men at arms (drawn from the mercantile elite, heavily armed and armored) and a large force of crossbowmen (more often drawn from those in the crafts). The towns have also developed representative badges and seals to denote and display town affiliation and pride. These badges, unlike the traditional two-colored sigils of the nobles, are often of a single color with a representative device imprinted upon it. The devices used can be related to the commercial activity most prominent in the town, reflect that of the local lord, or even be a visual pun on the town’s name.

Addendum to the Getting Medieval Town Article

Recommended Reading

For those interested in finding out more about towns in the Middle Ages, here are a few books that might help you get started. Unfortunately there is no real “friendly” text for beginners interested in this subject. The closest helpful layman’s work might be the Gies’ Life in a Medieval City, although this work deals less with small towns than with the substantial city of Troyes (which operated as a nearly independent entity within France) and focuses on a slightly earlier period.

Medieval England: Towns, Commerce and Crafts 1086-1348. Edward Miller & John Hatcher. Longman, London, 1995.

This immensely useful work is the second of a series on the social and economic history of England. It contains a wealth of information on medieval urban development from the time of the Domesday Book to the coming of the Black Death. The focus on the work is on the growth of urban centers throughout England in this time period, but it has some very useful information along the way and some wonderful facts and figures for those so inclined. Chapters five and up are more relevant to this month’s article, but previous chapters on trade and commerce should not be neglected. This is a more serious and scholarly work and its organizational structure is complicated at best, and so it is not really recommended for those with only a casual interest in the subject.

The English Medieval Town. Colin Platt. Granada Publishing, London, 1979.

Colin Platt is renowned for his archeological work on Medieval English architecture, and this book is a testament to his copious knowledge of the subject. It contains myriad diagrams, maps, photographs and other useful visual aids, and is a valuable resource for this reason alone. Unfortunately the illustrations are just about the only reason to look at this book, which is highly disorganized and light on useful information. Still, if you want pictures and diagrams this is the book for you.

English and French Towns in Feudal Society: A comparative Study. R. H. Hilton. Cambridge University Press, 1992.

This comparative work by the eminent social historian R. H. Hilton provides a framework for understanding the way medieval towns operated amidst the larger feudal landscape. It nicely highlights how they were both a part of and yet distinct from the larger social structure of the age. The information on French towns and his comparison of these urban centers with those of England brings out the uniqueness of the English experience and provides insight into the wider European urban experience.

Standards of Living in the Latter Middle Ages: Social Change in England c. 1200-1520. Christopher Dyer. Cambridge University Press, 1989.

A wonderful work which encompasses so many subjects, those interested in the Medieval English town will want to at least take a look at chapter seven, “Urban Standards of Living.” This chapter contains as much useful information as any of the books listed above, and has some very useful diagrams and charts. †

Just a quick note about town vs city designations in the Middle Ages. It has absolutely nothing to do with population. Cities are marked by the presence of a true cathedral (massive, not to be mistaken for primary parish churches, which are about half that size) from which a bishop rules his diocese. Cities are centers of Church administration.

Is it possible to get some elaboration on how you’ve grouped professions in your table of urban professions? For instance, would you put cobblers into clothes craftsmen or Leather workers?

Additionally, where would the city watch/guard fall on the same table?

Apologies if this information is found elsewhere and I’ve missed it!