Introducing The Vault

Above image © copyright Blender Foundation | durian.blender.org. Used under Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License.

What is the Vault?

The Vault is a game world designed to reflect the mechanics, character, and ethos of the Dungeons & Dragons game. It is a world created to reflect a game system, as opposed to a game system created to reflect a world. It is meant to facilitate the play of the game and to embrace the sometimes odd and quirky but endearing qualities that make the game so distinct.

You might ask how this is different from the regular way in which game worlds are constructed, but the answer should be readily apparent simply by looking at how many extra rules, classes, background packages and exceptions to the standard mechanics are present in almost every setting guide. The more one has to tinker with the game mechanics to make a particular setting work, the more friction there will be between the game world and the rules used to play in it. That doesn’t mean that the game world has to be boring. In fact, I would contend that a setting developed in this manner would be novel and interesting in the extreme, simply because world design is almost always approached from the other direction–that is, folks usually try to make up new rules or tweaks to existing ones so the game and setting will mesh. World designers seldom think about the implications the rules should have on the game world.

A world designed to fit the game system, we believe, can have all the wonderful history, character and detail of any other game setting.

Many years ago, just around the time 3rd edition was getting off the ground, Wallace Cleaves and Graham Scott created just such a world for running classic style D&D games for our regular RPG group. Our idea was to make a game world that reflected the relatively high fantasy nature of the game and to throw in some fun and fantastic elements to make it distinct. Several campaigns were run in it over the years and it has quite a bit of backstory and history. The Vault is not exactly that world, though it does contain echoes of that realm. Still, the experience of creating a world to reflect a game system instead of the other way around was so informative and enlightening that it serves as the inspirational forbear of The Vault. (Wallace and Graham have crafted a kind of agreement or contract permitting each of them to “spin-off” derivative materials from their earlier collaborations. The Vault is one of these spin-offs.)

Beyond the rules of the game there are also a number of environmental realities to the practice of gaming that have been, in an admittedly limited way, incorporated into this setting design. For instance, many DMs tire of a setting or want to bring in some new thematic element to their game. Often the only recourse is to scrap the current campaign and start anew. Alternatively, a DM might tire of the rewarding but burdensome chore of running a game and hand over the reins for a while, and be understandably reluctant to let his or her precious world be run by someone else.

Both of these are campaign killers, but The Vault contains a unique feature that makes such shifts and transfers entirely possible. Indeed, The Vault is specifically designed to be inclusive, to encourage rather than restrict the potential for any Dungeon Master to include new elements as inspiration strikes (though this might seem antithetical to the notion that the world is designed to reflect the rules, the hope is that certain design features make it possible to at least contain and explain such potential conflicts).

The Vault is designed to be a world of possibilities as varied and infinite as the potential of the game of Dungeons & Dragons itself.

The Physical World – Size Matters

First of all, the world of The Vault is big. Really, really big. It is not a singular spherical planet, but rather a kind of Dyson sphere. (If you don’t know what that is, look it up because it is a really cool idea.) Essentially, there is a sun in the middle of a giant sphere and people live on the inside of that sphere. The sphere is called The Vault because the whole world is encased in a visible dome that forms a sort of “vault” of the sky overhead. That is, the Vault of Heaven we speak of in the real world is both earth and sky in this one. (Don’t get all hung up on the physics; it’s a fantasy world after all. Not that we don’t have an internal–if somewhat fantastic–explanation for how and why it works. We do.)

Just to give you a reference point, the surface area is about 550 million times the surface area of the Earth.

So, yes, BIG. But, that’s not really all that important except for how it affects the people who live in the world directly. There are several things that are fundamentally different in The Vault. One big change is that the sun never sets. Instead, it dims each evening and turns into something like a full moon. People still call these two phases the “sun” and the “moon” respectively as everyone came to The Vault from somewhere else and they remember the concepts. There are a few more complications, such as variations in the length of sun and moon cycles to account for seasons, an occasional darkening of the sun or moon, and some other weirdness, but that can be saved for later.

This big world has big geography but it also has detail and focus. The first and primary region to be developed in this series is known collectively as specifically as the Basin Kingdoms. This very large area, incorporating dozens of minor countries and civilizations in its own right and stretching for hundreds of miles, is dominated by a central geographic feature, the river Rin. The Rin is a truly vast freshwater river that is more than ten miles wide for almost all of its explored length, and generally about fifteen miles wide in the Basin Kindoms.

The Rin River is so large that it really functions more like an ocean or a very large lake in many ways. The Rin is the lifeblood of the Basin Kingdoms and most regional trade takes place along its length either by way of the river itself or along the Great Causeway which runs a bit inland but parallel to the river along the Sunward shore. (By the way, that’s a direction, since north and south don’t really mean anything in The Vault. Sunward is a sort of mutually agreed upon north, and Moonward is its opposite. East is Earthward and west is Waterward. However, the old terms of north, south, east and west are also still used fairly interchangeably.)

Design Feature. The inherently fantastic nature of the geography of The Vault is intentional. It symbolizes and manifests the contention that this is a high fantasy game. It also representationally reflects the fact that Dungeons & Dragons is a game that embraces an almost limitless imaginative potential. There is room in The Vault for everything and for everyone. The Basin Kingdoms provide a core experience and a fixed locus around which all of the variety of The Vault can be displayed.

Hexads and Soft Geography

The odd cosmology and huge size are not the only curious things about the world of The Vault. Though this next fact is not known to everyone, it is quite apparent to anyone who has traveled extensively or studied the geography of The Vault that the world is an artificial construction.

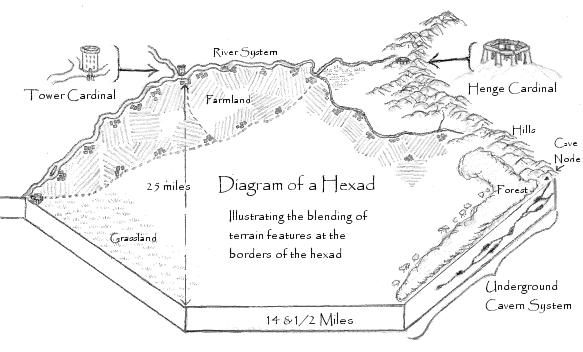

The feature that makes this artificial construction most apparent is the fact that the world is composed of regular hexagonally shaped areas generally referred to, among the savvy, as “Hexads.” Each of these hexads is 25 miles wide. That makes the distance between any two parallel sides of a hexad 25 miles. Each of the six individual sides of a hexad is 14 and a half miles long (actually 14.4337 miles) and the distance between two opposite points of the hexad, the depth of a hexad, is 29 miles (28.8675 miles exactly).

This curious composition is not obvious on the ground as each hexad abuts relatively seamlessly with the next and the terrains blend together at the borders. Each hexad tends to have a dominant physical characteristic that is featured throughout its area. For instance, a single hexad will tend to have mountains throughout its area, while another will be dominated by plains. At the borders of the hexads contrasting features tend to blend together, but there are some examples of sharp differentiation which make the artificial nature of the world more obvious. In many ways the hexads operate like small, independent tectonic plates, and thus the borders between hexads are sometimes marked by more extreme geographical features. There are quite commonly hills, rivers, or fissures between hexads of differing characteristics. Particularly, most rivers in The Vault flow along the borders between hexads.

Each hexad also tends to support a specific microclimate as well. The vegetation and the creatures within a single hexad will be fairly consistent as will the mineral content of the soil and even the general climate. This makes the borders between hexads, particularly ones with substantially different microclimates, locations of atmospheric disturbance. There are often mists, updrafts and even more violent weather phenomenon at the borders of unlike hexads. Still, most hexads abut other hexads with similar geography and climate, so the fractured nature of the world is not as obvious as it might be if there were frequent and radical shifts from hexad to hexad.

The border regions between hexads have some of the most geographically interesting physical features, particularly where unlike hexads meet. The points where three hexads meet, known as “Nodes,” are particularly remarkable. Nodes tend to have more fantastic and remarkable geographic features than their surroundings and may be marked by hills, springs, river confluences or other major features. Nodes are often the site of monuments or structures, particularly of temples menhirs or dolmens. These structures are often built to take advantage of the raw magical forces that flow along the borders between hexads and concentrate at the nodes (much in the way that ley lines and nexuses work in other worlds).

These node structures have another purpose as well. In a very real way they hold and bind the hexads together. Not only is The Vault an artificial construct, it also lacks a conventionally stable geography. Though the process by which this occurs is not at all fully understood, hexads within The Vault sometimes change their relative geographic location. Hexads can shift or move, making the large scale terrain of The Vault functionally unmappable and unstable. This trait has come to be known among sages as “Soft Geography,” and has had a number of curious effects on the cultures that have sprung up on The Vault. However, this odd characteristic is not as disturbing as one might expect since hexads seldom move too far in terms of their relative position, most often only swapping places with their nearest and most similar neighboring hexads. Also, these shifts do not happen frequently, though they are more common during the major cosmological events of The Vault (see the calendar section for details). Some fairly large areas of The Vault are also entirely stable and some large geographic features, such as rivers or mountain ranges also tend to lock down the geography of specific regions. Indeed, soft geography is most apparent in uninhabited or sparsely populated regions. In the deep wilderness, far from civilization, the geography can become completely unstable, making travel through such soft geography quite uncertain and even dangerous.

Of course, many people in more civilized regions of The Vault remain unaware of soft geography as there is a not fully understood mechanism that makes inhabited hexads much less likely to migrate. Additionally, sages long ago discerned specific magics which could lock particular hexads in place. Particularly, any three hexads could be linked together at a node by the construction and enchantment of a monument. Many such monuments litter the landscape of The Vault, often taking the form of menhirs or dolmens, or in more civilized regions appearing as temples or towers. These are collectively called “Cardinals” and are almost universally circular in shape. The magic in them has to be periodically renewed through rituals for them to remain fully effective, though even dormant cardinals tend to ameliorate the effects of soft geography a little. It is also known that roads between two hexads tend to bind them together, particularly when they are frequently traveled.

Nevertheless, there exist certain individuals, known as “Wayfinders,” who have a natural ability to navigate the soft geography of the hexads. They seem to be able to inherently sense the presence of the borders between hexads and are particularly sensitive to nodes. They are also able to navigate, more or less reliably, between unfixed hexads, even traveling through large regions of soft geography. This makes them very valuable as scouts and explorers.

Design Feature: “Soft Geography” is a principle used in a variety of ways in a number of game worlds Graham and Wallace have designed, as it makes possible all kinds of inspirational and tonal shifts and potentialities. It inherently allows for changes to be made to the world without destroying it. Soft geography makes it possible to move campaigns or change DMs without disrupting the continuity of the player’s experience. It is also a wonderful MacGuffin with all kinds of narrative potential to introduce new and exciting vistas while still maintaining a connection to the campaign’s core. Finally, it is a perfect mechanism for those who wish to imitate the into-faerie, or into-the-forest, genre from Classical, Arthurian, Medieval, and Renaissance texts: The sorts of stories in which heroes leave civilization and enter a wild, mysterious, fantastic space that seems to operate by its own rules.

An Ancient and Strife-Filled World

The age and instability of The Vault means that the world is littered with ruins, ruins of towns, cities, even whole kingdoms and civilizations. The Vault is also decentralized as it is difficult to maintain large and far spanning empires in a world where the basic geography may occasionally shift. Additionally, the massive size and unstable geography of the world engenders a peculiar tendency towards large scale migrations and incursions. After a cosmological confluence, two heretofore distant and ideologically opposed kingdoms may find themselves existing as new and antagonistic neighbors. Such moments often lead to strife and conflict as the two new cultures struggle for dominance. In the ensuing destruction, whole sections of a culture may break away and find themselves adrift in a new geographic region. This also means that cultures from one part of The Vault may be dispersed and encountered elsewhere with fairly regular frequency.

Huge monsters and hordes of humanoids are also a significant problem throughout The Vault as the sheer scale of the world makes it possible for massive migratory groups to gather and roam through the ever shifting geography. Occasionally a draconic pack or an orc horde will will stumble upon some pocket of civilization and conflict will ensue.

Since so many invasions happen, many holdouts and fortresses exist, sometimes falling into enemy hands, sometimes hanging on out there in the wilderness on their own for decades until rediscovered. Some turn into lairs for former invading forces, some into the dens of creatures.

In other words, dungeons are all over the place. Some of these ruins are very, very old. In fact, some sages believe that The Vault is the first and oldest of all the worlds and planes. Regardless of the truth of these rumors, there are certainly many ancient and pre-human ruins about.

Design Feature: The size and malleability of The Vault’s physical structure–and the consequences of those features upon the societies and cultures dealing with them–help explain or at least rationalize a number of sometimes problematic features of D&D. It is hard to explain the ecology of a dragon in a world of more limited scope, but in The Vault it is possible for flights of the creatures to roam forth and find plenty of elbow room. Dungeons often seem an illogical or at least wasteful use of resources, but in The Vault they are a necessity. Likewise, the infinite and changeable nature of the world helps explain why new and unexplored ruins might be happened upon by adventurers on a surprisingly frequent basis. Finally, the regular apocalyptic incursions provide spectacular fodder for epic campaign arcs.

The Moric Civilization

Because the world is so vast and because the geography is so unpredictable, it is sparsely settled. There are unexplored areas of wilderness the size of many whole worlds. In fact, from any settlement, the known world is relatively small as sporadic invasions of monsters, hordes of humanoids, and other civilizations periodically wipe out contact among settlements. Still, a few civilizations have adapted to the odd circumstances of The Vault and found ways to flourish.

Ages ago, the Moric civilization, a fairly advanced feudal culture that worships the metallic dragons, stumbled upon a sort of “defense in depth” strategy to surviving. They actively placed little outposts on frontiers and in bordering hexads. These would grow and cast out satellite settlements around them, slowly civilizing a region and geographically binding it together. Sometimes these outposts would be wiped out in an invasion, but sometimes they would survive while the center was destroyed and become their own locus for the next generation of expansion. Some of these outposts would even become cut off from the main culture and drift, through the agency of soft geography, and become new hubs of Moric civilization and culture in far off corners of The Vault.

This has led to the widespread dispersion of a central Moric culture throughout significant portions of The Vault. Many realms have at least a colony of Moric settlers somewhere on their borders or even incorporated into their own civilization. Several very large Moric empires have also managed to achieve surprising longevity and stability. The culture is assisted in this by three significant advantages.

The first is that the culture is generally lawful and good in alignment, largely as a result of their association and idolization of metallic dragons. The tendency of Moric cultures toward organization and altruistic cooperation has made them strong and united in the face of fairly chaotic world. This enlightened culture is also supported by a strong martial tradition and a faculty for powerful magic, perhaps also inherited from the draconic idols the Moric people hold as their inspiration and who they believe are their distant ancestors.

The second trait that has enabled the success of the culture is its relative diversity and acceptance of outside influences. While the Moric culture has a strong central ideology, it is essentially inclusive and embraces other races and cultures. Indeed, two of the core families that comprise the Moric, dragon-descended nobility are non-humans. The Ferrum family of dwarves and the Cupric family of elves are fully integrated into Moric culture, comprising two of the seven houses that form the traditional nobility. Other non-humans of good or at least neutral persuasion have likewise been welcomed into the culture and significant populations of halflings and gnomes are present in most Moric settlements. Even more exotic races and individuals are likewise welcomed as long as they maintain the core values of the civilization.

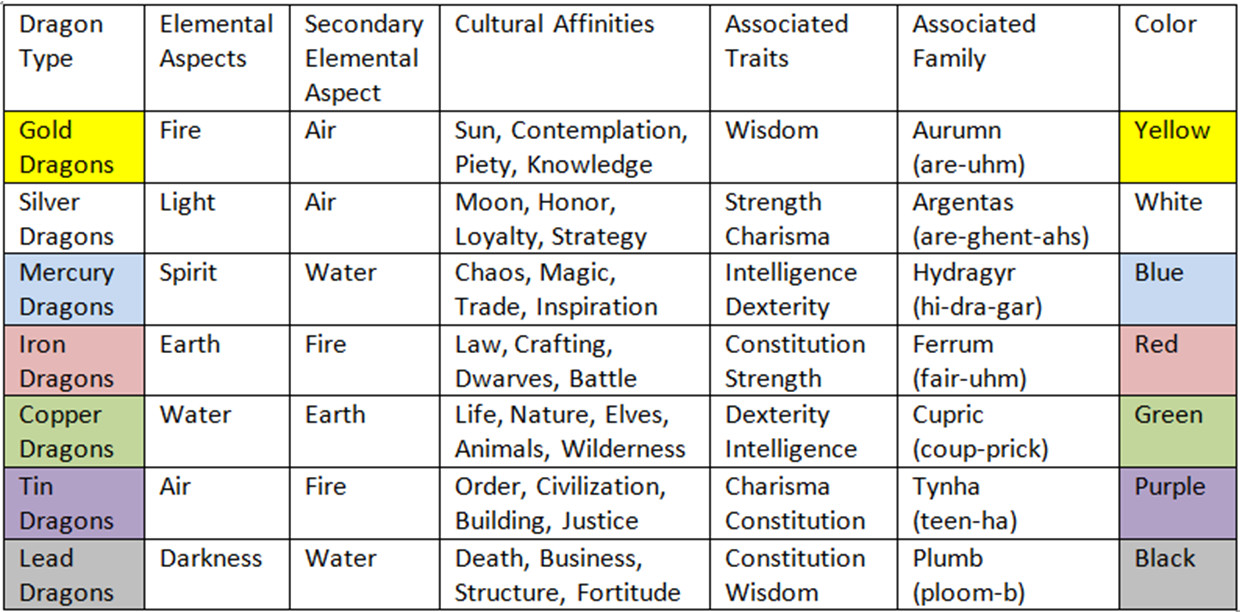

The third trait that has sustained the Moric culture is the effective specialization of the different draconic houses. Each of the seven houses has specialized in particular important social and cultural responsibilities, refining the essential elements of civilization and working together in unusual harmony. The specialization of the houses has allowed each to assume a prominent cultural role without treading on the others:

- The Aurumn claim their descent from gold dragons and are a priestly, even monkish, class of contemplative leaders. They have a strong meditative and anti-materialistic streak that has allowed them to maintain a central leadership role in the culture without alienating the other houses.

- The Argentas are descended from silver dragons and are the military officers and paladins of the Moric culture. They have an intense and selfless devotion and loyalty that has allowed the other houses to rely on them without feeling threatened by their military prowess.

- The Hydragyr are descended from the Mercury dragons and dominate the fields of magic and trade. Their arcane and economic power is tempered by their somewhat overactive and outgoing disposition, putting the other houses at ease with their control of these essential cultural forces.

- The Ferrum are a dwarven clan that claims descent from iron dragons and that have become fully integrated into Moric culture. They are master craftsmen and stout heavy support warriors. Despite their nonhuman ancestry and slightly taciturn nature, their loyalty and conviction to the metallic dragon cult that suffuses Moric culture has made them an essential part of the society.

- The Cupric elves are descended from the verdigris copper dragons and owe allegiance to Moric culture and their draconic forbears since their own elven kin failed to protect them in the distant past, during the great elven schism, a mysterious event shrouded in ancient elvish history. (When elves think of something as shrouded in ancient history, that’s saying something.) They are masters of woodcraft, skilled hunters and help patrol the wilderness that surrounds the Moric outposts.

- The Tynha are perhaps the most problematic of the houses. They are descended from tin dragons and have a strong association with order, law and organization. They are a somewhat officious group that makes up the majority of jurists, police, clerks and bureaucrats, and while they may not be loved the value of the services they provide are appreciated.

- The Plumb are descended from lead dragons and have a great facility with transportation and trade, especially on water, and with building, a passion shared to a lesser extent by the Tynha. They have a somewhat dour and pedestrian reputation, but they are also doughty and stolid with little passion or ambition, making them stalwart members

The society that has evolved from the alliance of these houses has proved a formidable and enduring force through many regions of The Vault. While whole Moric civilizations have fallen to invasions and incursions of monsters, the society itself survives in numerous small pockets and in several sizable empires spread throughout The Vault.

Design Feature: The Moric culture is meant to serve as a connective thread that can exist anywhere in The Vault. Its spread and ubiquity provide a kind of base from which other, more disparate cultures can distinguish themselves. Characters from the Moric culture can logically exist in any campaign set in The Vault and are thus the standard, the center and fixed point that provides reference for the infinite possibilities of the world. The Moric culture also embodies several fundamental characteristics of the D&D game itself, giving a home to each of the iconic classes (as will be discussed in detail later) and enshrining the multi-racial (in the true sense of that word) nature of the game by making dwarves and elves inherent elements in the dominant culture.

Then there is the draconic influence. Here is one area where, admittedly, the rules (or at least the core ethos of the game) are being played with a bit. This honestly springs from a pet peeve being writ large upon the world in that the absence of iron dragons in the D&D games and the odd inclusion of the alloy dragons always seemed a bit off. Still, there is careful logic behind this design choice. Dragons are such an integral part of the game that they are eponymous. We wanted them to figure prominently in the design of the world. We had also long recognized through study of comparative mythology a fascinating, historically-potent, symbolic pattern of cultural tropes and themes that divided the worlds of magic, the gods, and even culture itself into seven distinct influences or “spheres.” Most people are at least familiar with the seven days of the week and the seven “planets,” as well as the divinities they are associated with. But in the mythology of any number of cultures, these seven “spheres” are more than simple astronomical signs. They are a symbolic representation of universal principles. Conveniently, each is also traditionally associated with a specific metal, sometimes explicitly (as is the case with Mercury, associated with Hermes, and with Tin, which is derived from the Etruscan name for Jupiter or Zeus). It seemed an elegant and even natural fit to link these spheres with the metallic dragons that are part of the game’s core mythology and in so doing fuse the cosmology of D&D with that of its most clear cultural analogue.

Recent History – The Dwindling

As noted, invasions and disruptions are a common phenomenon in The Vault, and a particularly violent one happened about twenty years ago throughout many regions of The Vault, hitting the Moric cultural Imperium of Mor Shorizon and the Basin Kingdoms particularly hard.

The event in question is generally referred to as the Coming of the Fiends, or the Infernal Incursion, or more poetically as the Dwindling. (The solar orb dimmed and even blacked out for a portion of the disturbance.) Huge forces of supernatural creatures including fiendish and demonic forces and powerful chromatic dragons invaded the capitol and main cities of the largest single Moric dominion and wiped out much of the central authority that had held the region together for centuries. The capitol city, Mor Shorizon, was completely cut off and its fate is still unknown. Many other cities along the Rin suffered catastrophic damage as well, but the tide of battle turned when a group of legendary heroes, long thought dead (or even possibly mythic), returned and destroyed the main invading forces before vanishing again.

It took years for the local powers to mop up and reestablish contacts and begin to recommence trade and relations. With no central authority from the capitol, the Basin Kingdoms once again became actual kingdoms, separate and sovereign. They are still loosely allied, and widely enough spread out that major conflicts are fairly rare, but the central authority that held the dominion together is gone. The wilderness is also just a little bit wilder as the lack of central authority and the death toll from the invasion essentially halted the settlement program. Bandits, humanoids and monsters lurk on the frontiers of each independent city state or Duchy, and travel between settlements is hazardous at best.

Design Feature: It can be helpful to have a historical benchmark in recent game world history, a point from which to measure all other events. As the world lends itself to cataclysmic disturbances, we wanted to have one in the recent past, but far enough away that a sense of normalcy and continuity might have been restored. Furthermore, the Dwindling rationalizes the presence of some more extreme monsters in the region and provides a host of opportunities to recover the faded glory of a once mighty empire–a quintessential theme of so many fantasy settings. However, the Dwindling is also meant to rationalize the sense of recovering ancient wonder without indulging in the malaise of the “fading world” trope that also haunts so much of fantasy. The Vault is a more upbeat and vital realm than those dimming worlds where magic is rare and marginalized. Civilization may have taken a step back recently, but it is now determined to move two steps forward.

The Basin Kingdoms

Mor Ithel and Mor Gilos are two very large metropolises, connected by a stretch of the Rin River, that once belonged to the Imperium of Mor Shorizon. The two cities and the settlements of the river basin are known as the Basin Kingdoms.

Though affected by the recent incursion, this area remains relatively stable and returned to a relative normality in the wake of the Dwindling. To be sure, the central authority that Mor Shorizon once exerted is now absent, and the two poles of Mor Ithel to the waterward and Mor Gilos to the earthward now vie, politely for the moment, for suzerainty over the intervening regions. Even the smaller holdings between the two great cities are more independent than they previously were and some principalities and dukedoms have begun to establish and pursue local and regional authority.

As of yet this fragmenting has not led to serious hostilities; the Moric culture is inherently fragmented and feudal, granting much local authority and autonomy as a matter of course. Still, the situation is inherently unstable and several local conflicts are brewing that might lead to more widespread strife as new alliances and power structures are built. The once figurative regional name of the Basin Kingdoms, stated in the plural though it is just one kingdom for now, may indeed become an even more apt moniker in the near future.

The Basin Kingdoms region is relatively geographically stable, at least within a hundred miles or so of the Rin River. The name of the region is derived from the presence of two massive mountain ranges that parallel the Rin River to the sunward and moonward, forming a basin from which many smaller tributary rivers flow into the massive confluence of the Rin. The sunward mountains are known as the Dragon’s Wall range; the moonward range is called the Border Mountains. Between them, stretching for hundreds of miles, lies the fertile river valley of the Rin.

The Rin is a truly massive freshwater river that is at least fifteen miles wide where it flows through the Basin Kingdoms. The river is incredibly vast but it serves as an effective conduit for people and trade goods along the entire stretch between Mor Ithel and Mor Gilos. Though massive, the river has a gentle current that flows at about eight miles an hour near the center, and quite a bit slower near the shore. A reliable wind also fortuitously blows upstream from waterward to earthward making the use of sail craft possible. The river forms several larger “lakes” during its gentle meander through the Basin Kingdoms region, particularly in area where other large river systems join the massive waterway. The Rin is also plied by several large floating cities, the primary two being Fleet Arcis and Fleet Prasis. These fleets stop at many settlements along the Rin, providing temporary access to a thriving metropolis for even the more scattered settlements. The river itself is home to some impressive mega-fauna, including the dread Iron Gar, the gentle but enormous Leviathan Mudfish, and the occasionally pesky giant snapping turtle.

The whole area is settled, more densely near Mor Ithel and, to a lesser extent, near Mor Gilos, but there are patches of relatively sparse population near the middle of the region, especially in the wake of the Dwindling. Ages ago this area was home to many small, independent kingdoms along the river with many more settlements and outposts up the tributaries of the mighty Rin. For the last few centuries the whole region has been under the dominion of the Imperium of Mor Shorizon, but it has retained an inherent characteristic of self-determination and local government that served well in the wake of the Dwindling. The region has largely recovered from that tragedy and a new age is dawning.

The Sept

The first specific local region that will be intimately developed as a regional setting is a former Duchy, now an independent state (though the ruler maintains the traditional title of Duke) known as the Sept. It is a collection of seven towns clustered along the Rill and Wend rivers, tributaries of the mighty Rin. It is separated from other regions by two large rivers that feed the Rin, the Green Water to the MoonWaterward (southwest) and the Lefflow to Earthward (east) beyond which lies the massive Deepwod. In the Sunward (north) direction massive mountains of an outcropping of the Dragon’s Wall range rise clustered around a huge peak known as the Pinnacle. To the Waterward (west) lie open expanses of vast, unsettled land. The more Sunward portions of this frontier become dry and turn to desert while the more Moonward portions become vast open plains filled with countless herds of large beasts and roamed by savage tribes. The Moonward border is the Rin from which most contact with the outside world flows.

Design Feature: Every game world has to start somewhere, and every campaign has to have a home base. Both the Basin Kingdoms region and the specific setting of the Sept are designed to provide a home base, itself a potential source of motivations and adventures, from which characters can branch out and explore the (oh so much) wider world.